Small-scale research into how pronunciation can be improved in the new normal using state-of-the-art methodology

The challenge of integrating the pronunciation component into lesson design

Designing state-of-the-art lessons could be all but a challenge. Many teachers are faced with the need to cover the syllabus and so, simply focus on turning the pages of coursebooks to make sure no contents are left behind. Yet, following structured practices make me wonder whether our teaching leads to actual learning. Oftentimes, I still ponder how we teachers can maximise learning while making the process of teaching enjoyable, without having to carry the burden of knowing that diverting from any form of traditional form of teaching will lead to unrelated skills practice as well as untaught—or rather unlearned—contents. And I cannot stop thinking about what to do with the so-called "Cinderella of language teaching" (Dalton and Seidlhofer, 1994; Kelly, 1969;Underhill, 2010)., i.e., pronunciation. How could we make it find its “prince charming” so it is no longer segregated from L2 lessons?

Getting started...

Brian Cambourne (1995) developed a constructivist philosophy which states that the language skills (i.e., reading, writing, speaking and listening) are parallel manifestations of the same vital human function: the mind's effort to create meaning. As a teacher, I have always questioned the best pedagogies for teaching an L2. And I have come to the conclusion that, in a “Postmethod” era (Kumaravadivelu, 2006), we must change our mindset and start creating lessons that result in the authentic integration of the skills, while activating higher order thinking skills, fostering critical thinking, and developing linguistic awareness through self- and peer assessment.

With the above ideas in mind, I decided to break the mold and conduct a small-scale study to measure the extent to which two different pedagogical approaches had a greater impact on the development of key sounds for Spanish speakers, i.e., the English front vowels, /i: ɪ e æ/, which are considered high priority sounds (Kenworthy, 1987). As the Spanish vocalic system is considerably much more simplistic, this means that the learner will tend to use reduction (Corder, 1978) or assimilation strategies as a result of a magnet-like effect caused by the learner’s inability to tell the difference between L1 and L2 sounds which are apparently phonologically similar; in other words, L2 sounds that resemble L1 sounds will tend to be identified with L1 sounds (Best, 1995, Best, Faber, and Levitt, 1996; Flege, 1995).

The two pedagogical approaches

The aim of the study was to evaluate the impact of two different approaches for the teaching of pronunciation on the development of four key vowel sounds of English:A

- The Traditional approach, focused on imitation and repetition of decontextualized words or sentences.

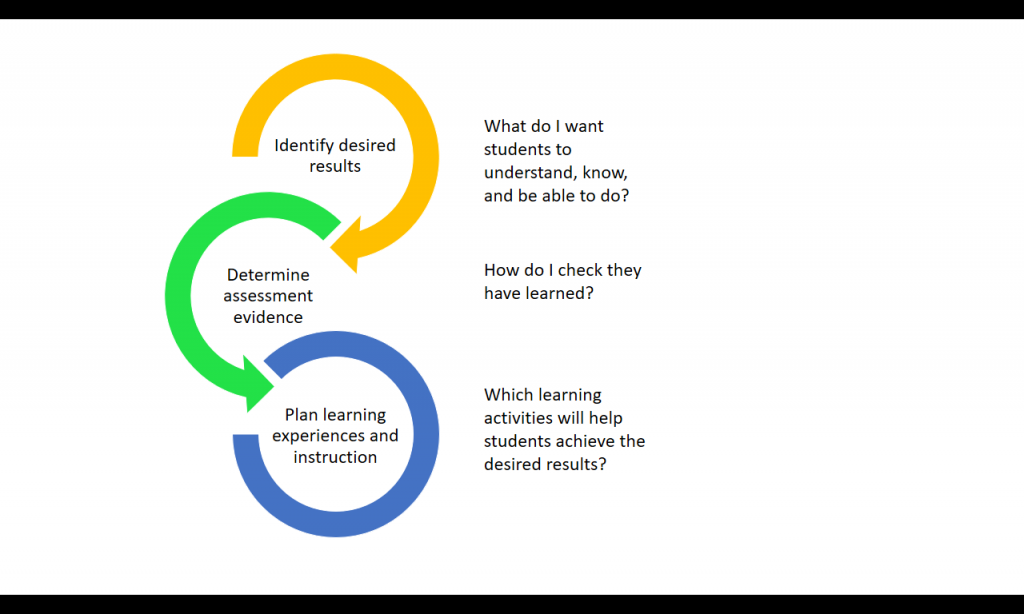

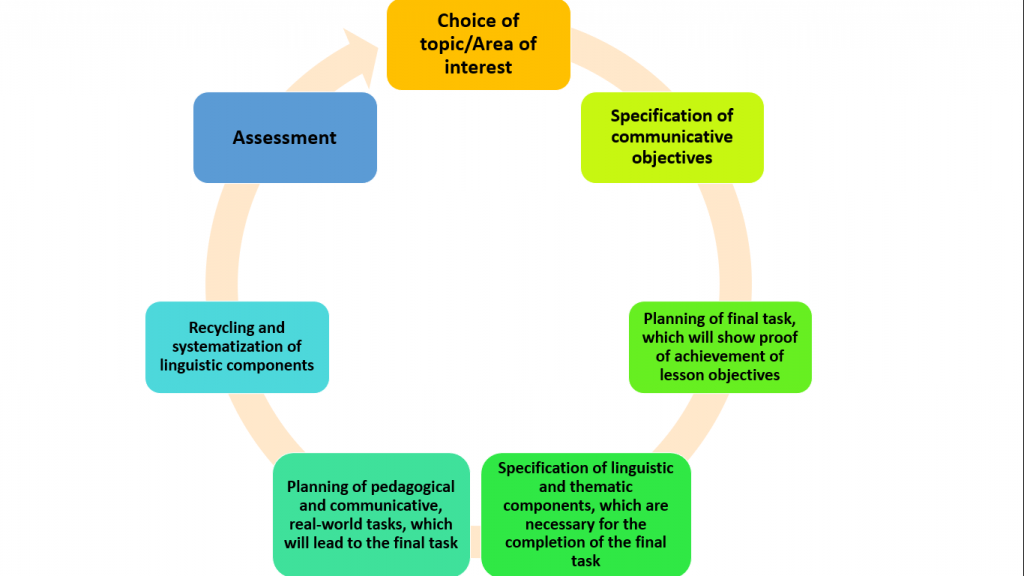

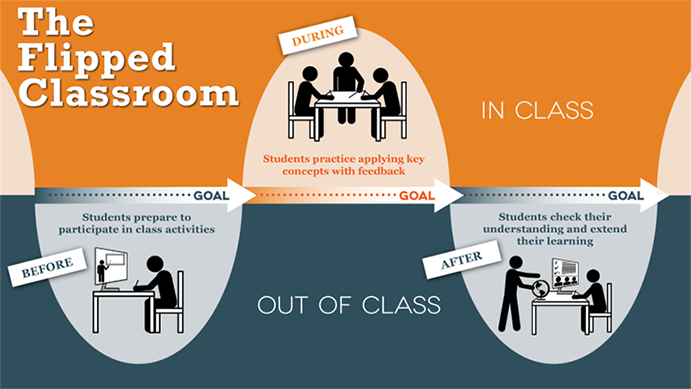

- An eclectic approach, which resulted from a combination of backward design (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005), task-supported lessons based on Estaire and Zanon’s framework (1990), the Flipped Classroom Model (Bergmann and Sams, 2012), an Integrated-skill Approach (Oxford, 2011), and COVID-19 and all the changes to be made on the instructional level.

The emotional rollercoaster of the pandemic brought about a new challenge: being able to teach with distance learners, both synchronously and asynchronously, and making sure there was ample practice and feedback, no matter the approach.

For the above reason, I decided to use Extempore as a digital language laboratory that would serve a two-fold purpose: it would become a portfolio of the student’s oral production and it would turn into a linguistic corpus.

Participants and Procedure

These two different pedagogical approaches were applied with sophomores pursuing a four-year degree in Translation/Interpretation and TEFL at a private university in Montevideo, Uruguay. Students (N= 28) were divided into two groups, Experimental group 1 and Experimental group 2, the former being exposed to traditional instruction and the latter to the eclectic approach described above. Simultaneously, both groups received systematic and focused instruction on the four target sounds to be developed using the Flipped Classroom Model so as to cater to learner autonomy and foster inductive learning. Participants were offered the same opportunities for oral practice (14 assignments), only that Experimental group 1 never had the chance to perform real-world tasks; participants would only stick to drilling isolated samples of the L2 in the form of words or sentences which contained the key vowel sounds. Experimental group 2, conversely, was required to complete a number of controlled and communicative (rehearsed and spontaneous) tasks (see sample lesson), which also included self- and peer assessment questions as a way to foster metacognition and critical thinking. All students were requested to review recordings and their professor’s feedback when necessary. The experiment took place in April-March 2020, when confinement was compulsory after the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 1 illustrates participants features:

Group features |

Experimental group 1 |

Experimental group 2 |

|

Average age |

24.07 (19-36) |

24.35 (19-39) |

|

Average years of exposure to L2 |

8.04 (6-12) |

7.92 (7-10) |

|

Gender |

Male |

2 |

2 |

|

Female |

12 |

12 |

Table 1: Features of Experimental Groups

How were results measured?

A post-instruction test was administered to assess whether students showed improvement or regression in the pronunciation of the target vowels. The test, which belonged to one of the sections of the pre-/post- test referred to above, consisted in reading sentences with the target vowel sounds in a consonant-vowel-consonant (voiced/voiceless) setting (see list of sentences below), to make sure that students were able to produce the appropriate vowel length depending on the context, i.e., there was vowel lengthening or clipping when the vowel occurred before a voiced or voiceless consonant respectively (see Table 2).

Controlled reading (sentences). Please, read the sentences below.

- I’m going to live with my brother.

- John beat the dog.

- There’s a band ahead.

- Here’s a cap for you.

- I changed the bet.

- Do you feel that?

- Have you got my pen?

- He wants to buy the ship.

| Word with target L2 vowel followed by voiced consonant | Word with target L2 vowel followed by voiceless consonant |

| LIVE | SHIP |

| FEEL | BEAT |

| BAND | CAP |

| PEN | BET |

Table 2: Word pairs with target vowels in C-V-(voiced/voiceless)C settings

In order to assess students, an inter-rater grader assessment was implemented. Two experts in the field of English Phonetics and Phonology (L1: Spanish) were asked to assess students’ performance using a Likert scale (1-9), 1 being a high degree of foreign accent and 9 being native-like accent, according to what Munro and Derwing (1995) suggest: “we believe our method of assessing both perceived comprehensibility and accent with a 9-point ratings scale permits a more appropriate comparison between the two data sets” (p. 92).

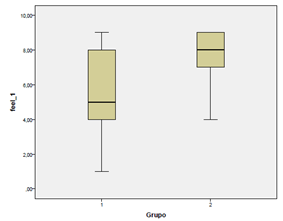

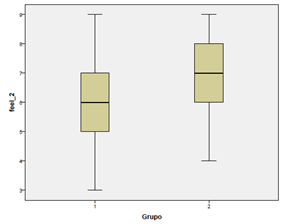

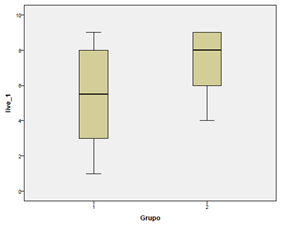

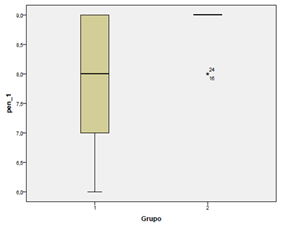

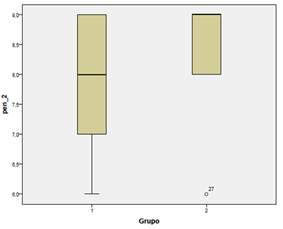

A Mann-Whitney test was run to check whether the results obtained by the inter-rater measurements were statistically significant. The test revealed that there were statistically significant improvements in Experimental group 2 in terms of the production of the target English vowels. The graphs below show some sample results, which indicate that the task-based methodology, which incorporated the use of digital portfolios and fostered metacognition and critical thinking through self- and pee--r- assessment proved beneficial and thus Experimental group 2 outperformed Experimental group 1. The graphs below illustrate the most significant differences between the groups:

All in all, as said before, this small scale research shows that the above-mentioned teaching approach for pronunciation instruction appears to be advantageous. Yet, limitations should not be neglected: considering the pre-test, together with new statics tests will need to be run not only to evaluate the degree of improvement or regression at inter and intra group level to actually prove that students made progress as a result of the teaching approach implemented is of utmost importance. In addition to this, acoustic measurements will have to be carried out to obtain objective results, which a Likert type of assessment does not produce.

Despite its limitations, the study conducted represents an interesting contribution to the field of Applied Linguistics, and the field of Translation/Interpretation and Teacher Training for a number of reasons. First, it has paved the way for studying segments (most of the existing research is based on suprasegmental features of English and is focused on speakers living in monolingual contexts, where English is a second language (Derwing and Munro, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2015; Derwing, Ron, Foote and Munro, 2012; Munro and Derwing 1995). Second, it will help teachers make decisions about which aspects of the L2 pronunciation to highlight according to students’ needs. Third, it will encourage teachers to reflect upon lesson design and material reflection. The pedagogical proposal evaluated in this study is based on a framework that integrates pronunciation with the macro-skills within a cycle of tasks, which consists of four phases: cognitive elaboration, where we will find sessions of focused instruction after the learner has had the chance to work on a given topic (in this case, the four English front vowels) on his own. The second phase associates, as it is here that the combination of pedagogical and communicative tasks will come into play. Pedagogical tasks will enable the learner to draw their attention to language phenomena and will scaffold for the subsequent communicative tasks. The third phase introduces autonomy into the language classroom, and it is at this stage that new knowledge and developed skills will be put at the service of communication. The last phase is that of re-elaboration as, through assessment, linguistic awareness will be raised (Sato and Ballinger, 2012) and recycling and the reconstruction of new knowledge networks will take place. Doubtless, flipping the language classroom (both for the teacher and the learner), using a combination of language focused tasks, on the one hand, as well as thought-provoking, integrative, tasks on the other, and including IT tools (before, while and after the moment of teaching) have shown to be favorable for the development of critical thinking and linguistic awareness. So it is probably time for a change in mindset so as to start creating more authentic, state-of-the-art Phonetics and Phonology lessons.

This is post was created by Cristina Chiusano. Dr. Chiusano is a Department chair at Universiad de Montevideo, Uruguay, an EFL instructor at the Teacher Training Program and Translation Degrees, Unversidad de Montevideo, and a Spanish teacher of online courses at Abiline Chirsitian University. She has a MA in TEFL and Spanish as a Foreign Language as well as a PhD(c) in Linguistics.

References

Bergmann, J. and Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. International Society for Technology in Education.

Best, C. (1995). A direct realistic view of cross-language speech perception. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross language research, p. 171–204. Baltimore: York Press.

Best, C., Faber, A., and Levitt, A. (1996). Perceptual assimilation of non-native vowel contrasts to the American English Vowel System. Paper presented at the meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Indianapolis, IN.

Cambourne, B. (1995). Toward an Educationally Relevant Theory of Literacy Learning: Twenty Years of Inquiry. The Reading Teacher, 49(3), p. 182-190.

Corder, S. (1978) Language learner language. In J.C, Richards (Eds.), Understanding Second and Foreign Language Learning: Issues and Approaches. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Dalton, C. and Seidlhofer, B. (1994). Pronunciation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Derwing, T. y Munro, M. (2005). Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach. In TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), p. 379-398.

Derwing, T. y Munro, M. (2008). Segmental Acquisition in Adult ESL Learners: A Longitudinal Study of Vowel Production. In Language Learning, 58(3), p. 479-502.

Derwing, T. y Munro, M. (2010). Symposium – Accentuating the positive: Directions in pronunciation research. In Language Teaching, 43(3), p. 366-368.

Derwing, T., Ron, T., Foote, J. y Munro, M. (2012). A Longitudinal Study of listening Perception in Adult Learners of English: Implications for Teachers. In The Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 68 (3), p. 247-266.

Derwing, T. y Munro, T. (2015). The interface of teaching and research: What type of pronunciation should L2 learners expect? In Luchini, P., García Jurado, A. y Kickhöfel Alves, U. (Eds.), Fonética y Fonología. Articulación entre enseñanza e investigación, UNMDP, p. 14-27.

Flege, J. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research, p. 233-276. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Kelly, L. (1969). 25 centuries of language teaching. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English pronunciation. G.B: Longman.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Munro, M. y Derwing, T. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. In Language Learning, 45, p. 73-97.

Oxford, R. (2001). Integrated skills in the ESL/EFL classroom. ERIC Digest. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics.

Sato, M. and Ballinger, S. (2012). Raising language awareness in peer interaction: a cross-context, cross-methodology examination. In Language Awareness, 21 (1-2), p. 157-179.

Underhill, A. (2010). Pronunciation is the Cinderella of language teaching. [Blog post] Retrieved from: https://www.adrianunderhill.com/2010/09/22/pronunciation-the-cinderella-of-language-teaching/

Wiggins, G. and McTighe, J. (2005) Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development ASCD. Colomb.