Over the past few months our blog has been on hiatus, getting some much needed R&R, following the footsteps of teachers and students every summer. While the blog recharged its batteries, installed new font drivers, and even added embedded tweets capabilities, the rest of us at Extempore geared up for our second annual PD Extravaganza and followed that with a summer-izing newsletter (okay, maybe that counts as a blog).

Rejuvenated and stocked with upcoming content, our blog takes center stage again. Back in the spring I wrote about ways to assess reading on Extempore and later followed that with the other input-based mode, listening. Before I knew it, we were halfway through the four skills, so the only logical follow up would be to write about writing and speaking assessments (this post), and thus we have a mini blog series on using Extempore to practice and assess the four skills in the WL classroom.

Here's what you'll find in this post on writing and speaking assessments:

- A Blog Breakdown where I briefly discuss writing and speaking assessments on Extempore

- Some background on discourse analysis, speaking, and writing in the world language classroom

- Factors to consider when assessing writing and speaking skills and creating practice opportunities

- Examples for both speaking and writing assessments on Extempore, paired with short Extempore Bites videos

Watch the Blog Breakdown below.

Adapting Discourse Analysis to Establish Context and Create Opportunities for Linguistic Processing

With approaches to language teaching changing throughout the past few decades and even centuries, many of us have adapted the modern method of communicative language teaching (CLT), where the classroom emphasis is not on proper conjugations, grammatical forms, or knowledge about the language, but rather on using the language to convey and understand messages. Olshtain and Celce-Murcia (2001) succinctly describe the rationale behind CLT:

The objective of language teaching is for learners to be able to communicate by using the target language, even if at times this is limited communication, and the most effective way to teach language is by using it for communication. So, given this premise, the goal of language teaching is to enable the learner to communicate and the method for teaching is for the learner to experience and practice relevant instances of communication. [emphasis added]

There's something missing though. In our classrooms, the communicative approach cannot succeed without discourse analysis, which puts aside sentences, grammatical structures, and pronunciation, and instead focuses on the overall course of an interaction and, according to linguist Deborah Tannen, what speakers do in conversation. This includes, as Tannen notes, linguistic discourse phenomena such as frames, or the lens through which we engage in conversation; turn-taking, or who speaks and who listens in conversation, and what determines that; discourse markers including filler words like 'um,' 'you know,' and 'well'; and speech acts, where the speaker goes a step beyond communication and does something, like makes a promise, tells a lie, or gives a compliment, all completed via language.

Where does discourse analysis fit into the world language classroom? Olshtain and Celce-Murcia (2001) outline four ways communicative language teaching benefits from discourse analysis.

#1 The text as the starting point

Unlike previous methods which focused on decontextualized individual sentences, discourse analysis prioritizes a full text (story, article, graphic, video etc.) as the starting point for language instruction. Instead of learning words and making single sentences through grammar-based repetition, students are presented with a text that they interpret for overall meaning. From what students interpret, they then can gradually acquire vocabulary and sentence structure, and eventually begin to use that language to communicate with their peers.

#2 Sociolinguistic features

The communicative approach to language teaching is centered around communication, obviously. Therefore, CLT necessitates various situations, both natural and contrived, for students to use the language. For example, students need to know how to greet others, and those greetings will vary depending on social status. Students will greet their peers by first name, but they would almost never greet their teacher this way. Some of this sociolinguistic knowledge, like how to address people, is already taken from their native language and culture, but there will always be cultural factors from the target language that students will have to learn in order to display cultural competence and proficiency. Thus, teachers should create scenarios that resemble real-world communication to best facilitate the practice and eventual acquisition of not just language but also cultural norms in the target language.

#3 Communication Strategies

All language teachers want their students to communicate in the target language. That's why we do this! The onus is on us educators, therefore, to provide communicative tools for our students to use beyond basic vocabulary and structures. After all, our learners are just that -- learners. They will be deficient in many areas, and we need to fill in gaps in communication where we can. Learners need "communication strategies that overcome and compensate for the lack of linguistic knowledge." Knowledge of appropriate gestures, circumlocution, clarification questions, rejoinders, and fillers are all examples of strategies we can equip our students with to become proficient communicators. It's language-specific scaffolding.

#4 Teachers as Sociolinguists

Finally, as we transition to a communicative approach and create tasks designed to resemble the real-world, we must go beyond simply being a teacher of that language. Teachers must assume the role of sociolinguists themselves, "aware of and interested in various aspects of discourse analysis," understanding our students' backgrounds and identities that will influence the ways they interact with both ourselves and their peers in the classroom.

Integrating each of these four points into our classroom, lessons, and assessments is the first step to laying the foundation of a communication-based learning environment. Likewise, when creating your own versions of the assessment examples listed below, you have a checklist for each item:

- Text-based: Does this assessment stem from a relevant text like a story, movie, or article?

- Cultural / sociolinguistic factors: Does this assessment consider any relevant cultural factors for the given context?

- Communication strategies: Have I equipped my students with the proper skills and tools to properly complete the task / assessment?

- Student backgrounds: Have I considered how student backgrounds might play a role in their responses to this task / assessment?

Assessing and Creating Opportunities for Writing and Speaking Practice on Extempore / Factors

Wait. Writing and speaking? I thought speaking came first? Indeed, when the two are spoken together, common parlance normally dictates the expression “speaking and writing.” In the quest for acquisition though, written proficiency will often precede spoken proficiency (as illustrated above). As such, proficiency for both skills can grow mutually, and while we at Extempore love extempore speech, teachers and students will benefit from building writing skills first. Consider the following:

- There's less pressure when writing. Learners don't have to worry about pronunciation or immediately responding to a prompt.

- Unlike with speaking, learners can check their written work and even correct mistakes from initial drafts.

- More time and less-pressure when producing written language means learners can better understand the prompt and produce an appropriate response.

The above factors share a common theme that should motivate us to prioritize writing - pace, timing, and pressure. With writing, students can produce a response at their own pace (within a reasonable amount of time, of course). High pressure environments create high pressure situations. There's countless research on anxiety in language learning and how it can inhibit proficiency; when we thrust students into speaking situations without requisite preparation, we are only increasing the pressure (and for some, feelings of resentment towards both the teacher and the class).

More time and less-pressure when producing written language means learners can better understand the prompt and produce an appropriate response.

All of this is by no means, however, to belittle speaking skills. To reiterate, they just take longer to build and grow. Speaking is often regarded as the last of the four skills to develop when learning a new language. The environment surrounding real-world speaking scenarios, when compared with writing, places different pressures on students as well. And let’s not forget: students take world language classes because they want to speak the target language. That’s the excitement that comes when walking through the door! Sure, they’re all super nervous about the prospect (and some will bring strong affective filters with them), but that’s the goal at the end of the day. So we acknowledge the difficulties and we prepare our students the best we can.

Let's look at some of those difficulties.

Students will always be conscientious about pronunciation, which they don't have to consider when writing.

There's an expected response time. Bygate (1987) describes how 'oral language allows limited time for deciding what to say, deciding how to say it, saying it, and checking that the speaker's main intentions are being realized.' This complex yet rapid internal process can be hard enough in our own native languages. Asking already anxious students to do this in a second language multiplies the pressure tenfold. We have to create the right environment and learning conditions prior to and during student speaking opportunities.

Classroom social factors and student chemistry also play an important role. When students speak in front of their class, they face judgment from their peers for both what they say and how they say it.

With general introductions out of the way, let’s look at some examples for each skill on Extempore. I should mention that there's overlap with each example below, meaning that a speaking task could easily be converted into a written one, and vise versa. When crafting these examples though, I try to keep them realistic: which scenarios will students actually encounter in the real world? For example, most of the time students will respond orally to something they listen to, and they’ll respond with text to something they read. Seldom is the case where we respond orally to a written message, or the other way around (I’m looking at you, voice messages).

Example 1 - Basic Practice: Question Response

Ask a question, get a response. That's all.

Q: What's your favorite sport?

A: My favorite sport is baseball.

Q: What grade are you in this year?

A: I'm in 10th grade.

Q: What classes do you have today?

A: Today I have math, English, and biology.

For questions like these, you can cloak them in an authentic scenario, but sometimes I need a quick formative assessment to ensure that my students can answer basic questions in the target language. This is particularly useful for reinforcing vocabulary and providing meaningful repetition, and it's a perfect end-of-class formative assessment that asks students "hey, we just did all this in class together, now can you do it on your own?" The answer to this question lies in their responses.

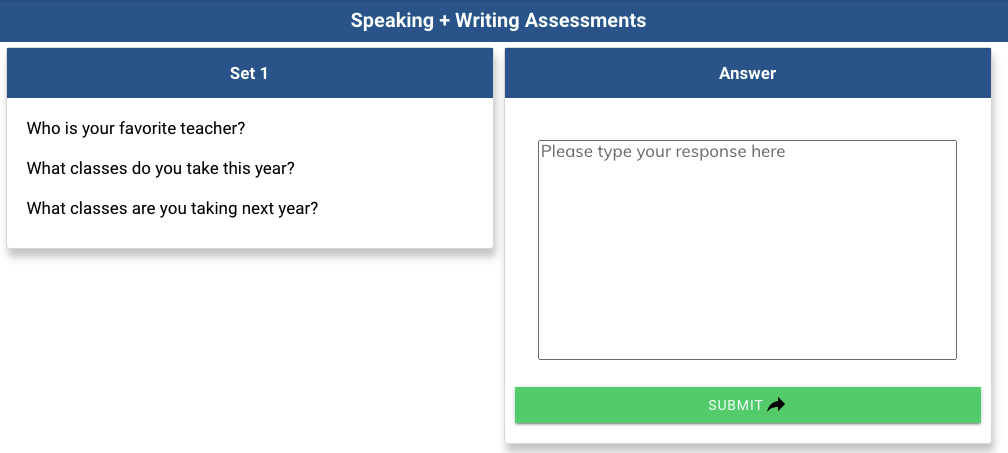

Pro tip. If you are asking novice questions that will have short responses, ask them all at once and have the student respond in one Extempore 'question. For example, if we are talking about classes, in one Extempore question (seen below), I might ask…

Who is your favorite teacher?

What classes do you take this year?

What classes are you taking next year?

When the question is designed like this, grading/feedback becomes much simpler: I can give comments (and scores, if applicable) to all three while saving time clicking through responses.

The overlap to speaking assessments is pretty straightforward here. Instead of having the questions written out, record yourself asking the questions in the target language (again, all three questions in one recording). The student then responds to all questions in one recording.

Example 2 - Communicative Tasks (Spoken + Written)

Communicative tasks on Extempore. They're here! They're there! They're everywhere. Authentic scenarios for students to produce the target language get students to see the relevance of what they are learning as well as their own skills at work. The category of 'tasks' covers hundreds of potential assessments, including

- Interpreting an infographic or other authentic resource

- Giving someone advice on what to do

- Making a decision based on provided information

- Composing an email

- Presenting a speech

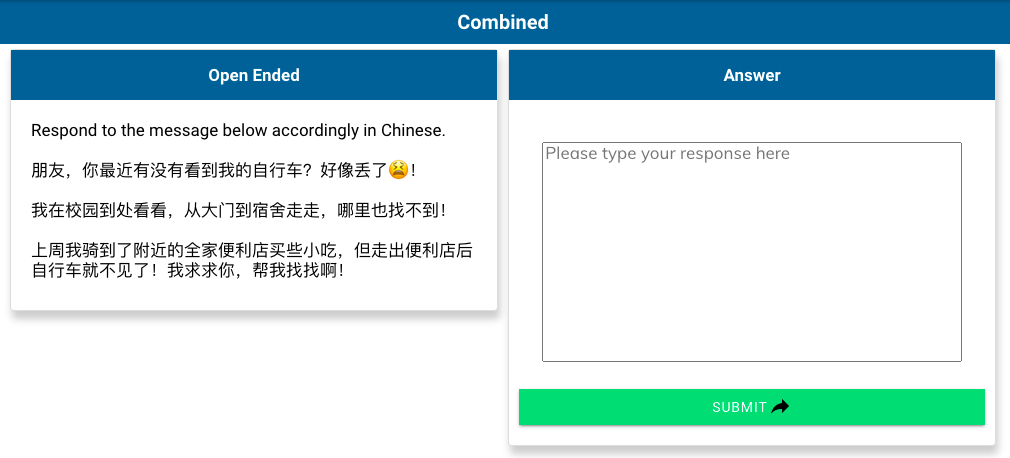

A basic message response question on Extempore

The list goes on. These assessments could yield both oral and written responses from students, so there will be plenty of overlap when creating these tasks. Specific items like email composition and speeches, however, will always require written and oral responses, respectively.

Pro tip: strive for to make your assessments communicative on Extempore. This means that the students are illustrating comprehension of the TL by either interpreting the TL or producing the TL. Assessments and activities should be meaning-based: the students should not be able to complete the assessment by simply parroting back the target language or filling in verb conjugations that don't require them to know what the words mean. Experiment with different questions and activities. If you're looking for inspiration, check out some of our recent blogs.

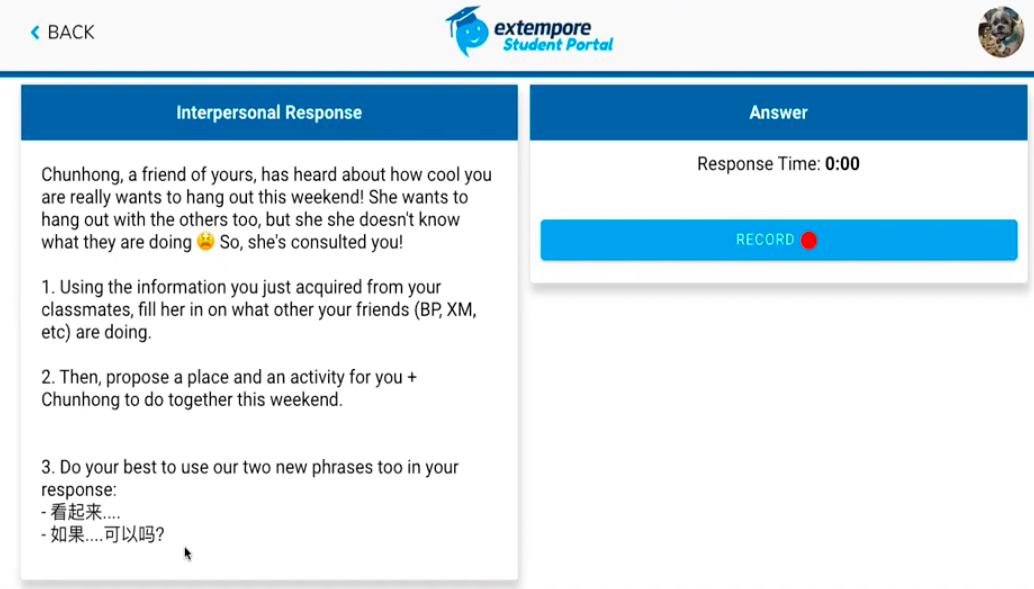

Example 3 - In class interpersonal / interpretive follow-up with 'level-up' words + phrases

First, I fully acknowledge that this example falls under communicative tasks, but it's worth mentioning given the various ways these can be used.

I started implementing these follow-up assessments last year after looking for a way to continue on an interpretive or interpersonal activity. For example, the interpersonal activity might have students ask one another about their favorite foods, and students would go around the room discovering their classmates' culinary preferences. In my first years teaching, students would finish and write a few sentences simply saying who likes what. But I realized that the task can be taken further, and I would ask myself 'what are students going to do with the information they've acquired from their peers?'

This question guided me to the follow-up task. In this case, instead of writing bland sentences, students would analyze their classmates' favorite foods and then determine what foods people should bring to a party if certain classmates were invited. By providing an opportunity for students to use the information they've gathered, you take the task a step further and provide a real-world lens on what's occurring in the classroom. Students immediately see the relevance to their lives.

What are students going to do with the information they've acquired from their peers?

What do these follow-ups look like on Extempore? Well, I love doing these so much that I hosted a specific session on them during our 2022 PD Extravaganza, which you can see below (use the timestamps to help find what you are looking for).

There's one unique factor in these types of assessments that differentiates them from typical assessments and activities on Extempore: in follow ups, students are consulting the results of the prior activity (interpersonal/interpretive) not on the Extempore platform while they are responding on Extempore at the same time. For example, they are looking at their survey results about favorite foods on one sheet of paper while also talking about those results on Extempore. This encourages students to spontaneously transmit analysis of the TL content they are reading into an oral response. Succeeding in this endeavor takes skill and proficiency, particularly on the spoken front.

The question on Extempore should include what students should be doing with the information they learned in the prior activity. Pro tip: add some level-up/function words and phrases for students to enhance their responses.

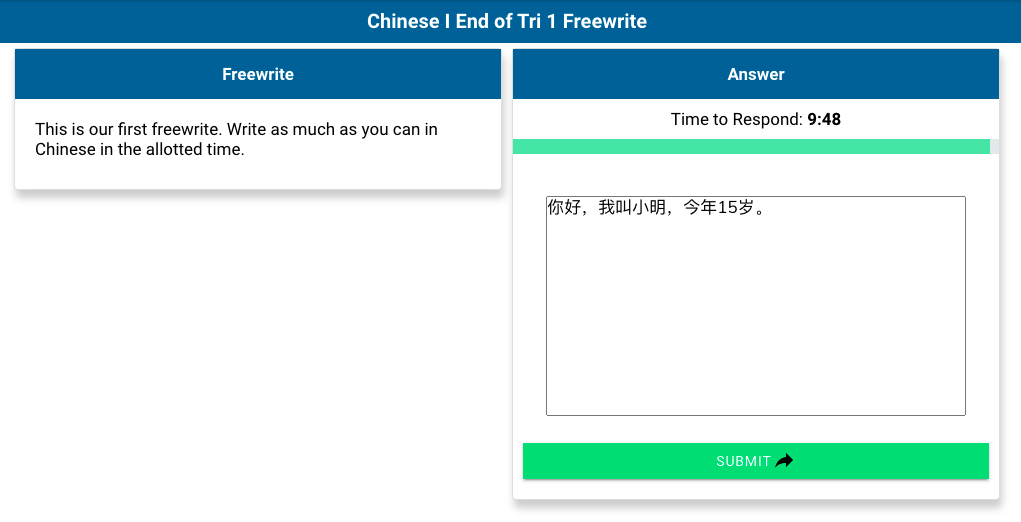

Example 4 - Freetalks / Freewrites: how much can you say?

If you've been hanging around our blog for the past year or so, you'll know that I've talked about freewrites and freetalks previously, both as their own post and in our practical proficiency in a pandemic blog and webinar.

The gist is simple: students write (or talk) as much as they can in the TL. For novice levels, they can talk about anything they want; the goal is just to produce all of the target language that they know. After all, the language that novice students can produce on their own represents a direct measurement of their proficiency.

For intermediate/advanced students, however, provide specific topics. At a certain point, we have to go beyond self-introduction and focus on topics like school, hobbies, jobs, food, etc. For example, when starting a unit on school, students will not possess the content-specific vocabulary to talk about school. The purpose of freewrites and freetalks, therefore, is to measure what they have acquired from the beginning of the unit to the assessment point.

Finally, by comparing freewrite results overtime, students can reflect on their linguistic progression and see the product of their learning in what they produce. The pride and introspection that students share in these reflections often reveal why we love this profession: to see students grow both communicatively and as learners.

Building proficiency starts with us

As I end almost every blog, I encourage you to experiment with the examples above to see what works for you and your students. Ask them for feedback and, when appropriate, heed it and adjust your assessments accordingly. Increased proficiency in assessment creation means we have better, higher quality assessments. In turn, these assessments give us clearer evidence of our students' levels and a blueprint for our next steps with them.

Works cited:

Bygate, M. (1987). Speaking. Oxford University Press.

Olshtain, E., & Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Discourse Analysis and Language Teaching. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 707–724). Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Inc.