I know, I know. Dictation? Yes, dictation. Sure, our students will likely never have to write out what they are hearing in real time outside of a school setting (are there careers as bilingual courtroom stenographers?), but that doesn’t mean there’s no use for dictation in the language classroom. Among its numerous benefits, a proper dictation is a reliable challenge for students and can help develop all four modes of communication. Dictations also require focus on part of the students, and their results can provide insight into student successes and shortcomings.

Poor results from a dictation can indicate a variety of teaching areas that need to be supplemented: word/character recognition, spelling (particularly with silent letters and homophones) and/or listening comprehension. On the other hand, strong results on a dictation task highlight students’ high listening levels and their ability to convert those sounds into text. Not to mention the extra typing practice that students get. Working with a new script, new alphabet, or just adding those pesky diacritics can take some adjustment, but like other pedagogical practices, repeated repetition with dictation can hone these skills even more.

Dictation: the Basics

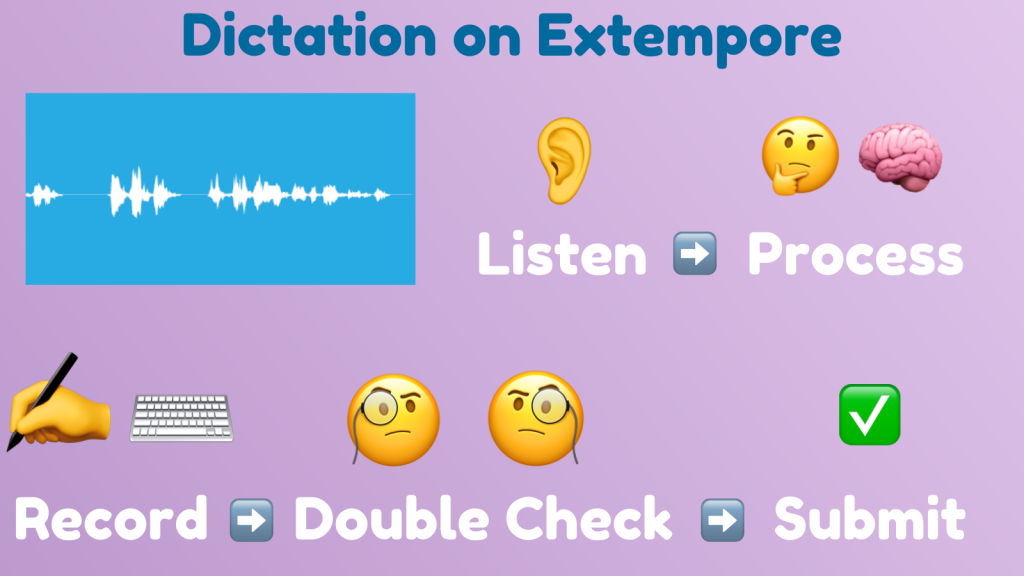

Before diving into the hows and whys and many methods of dictation, let’s take a step back. What actually is a dictation? In a dictation, there are two sides: the speaker and the recorder. More than likely the instructor will be the speaker, and the students will be the recorders, writing down exactly what the teachers says. Of course, students are not just writing random words but sentences, and they are also taking into account punctuation, spelling, and diacritics, while finally testing their short-term retrieval skills. Dictations may look simple, but there’s a lot of mental processing going on for students, and the instructor has an equally important responsibility to prepare. A proper dictation would flow as follows:

- Before giving the dictation, the instructor first picks a text of appropriate length and level.

- The instructor reads the entire text out loud.

- The students listen to the instructor, commit what they hear to memory, then record this language in written form, either on paper or in a digital format.

- In some cases, the instructor will repeat the text two or more times.

- As the instructor is repeating, listening students are comparing what they hear to what they have already written and correcting initial errors.

- On Extempore, students can play the dictation multiple times if the instructor permits.

- Finally, students come together and review what they recorded, comparing these to what the instructor read.

Dictations demand a high-level of cognitive performance for students to perform well. Students have to listen, store information (in a second language, mind you), then immediately recall it and write it down correctly. Depending on the length of text and the amount of times the student hears the instructor read it (as well as reading speed), this can be quite challenging! A challenge, however, that is well worth its benefits. Before getting into these benefits though, let’s clear up some things.

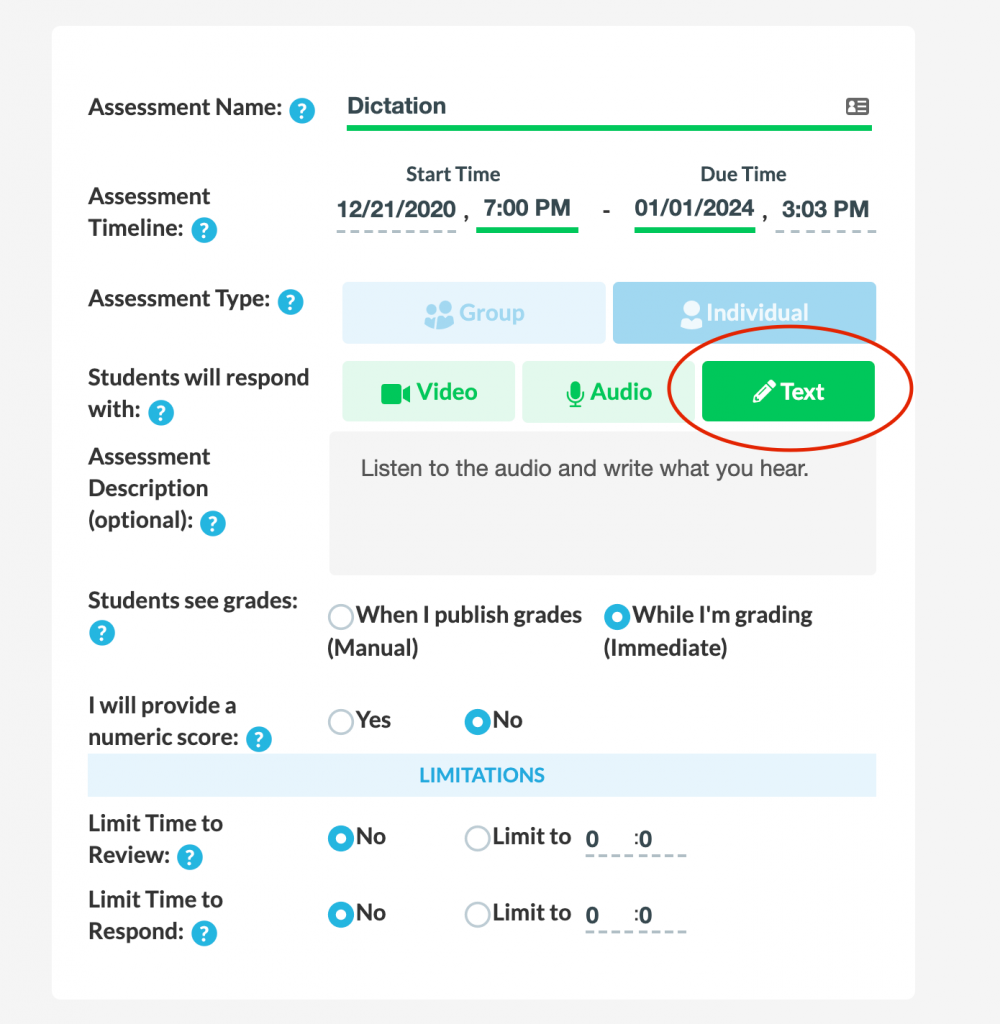

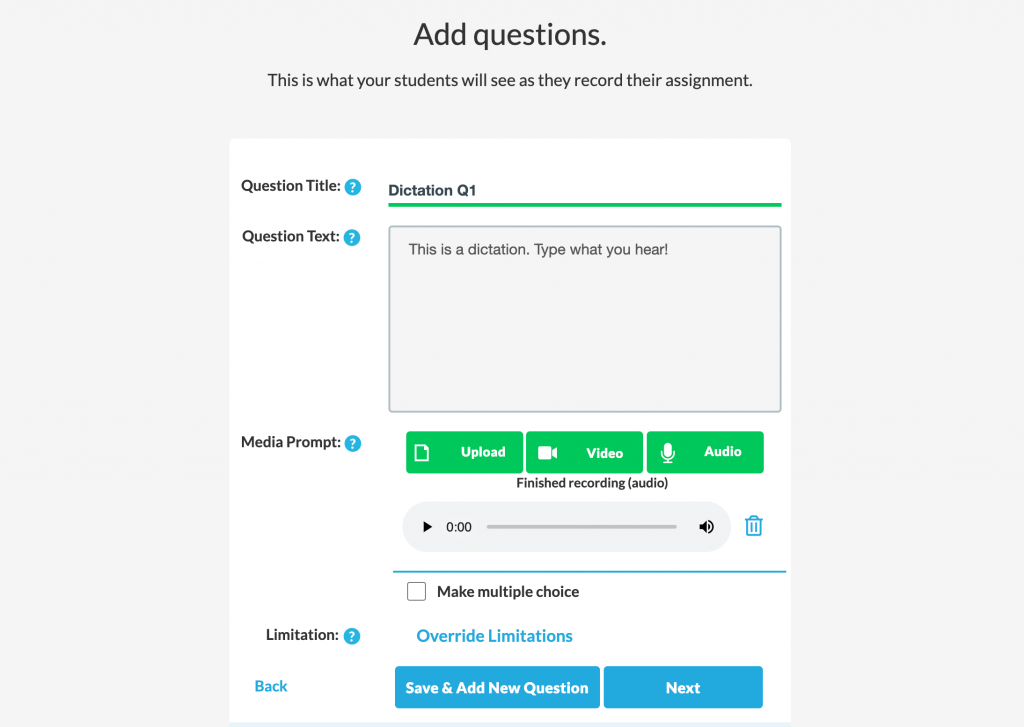

On Extempore, create dictations by first choosing 'text' as student response type. Then create questions by uploading a recorded audio file or by recording your own voice.

Aren’t dictations bad? And like, really old?

Why yes, dictations have been around for hundreds of years! But that doesn’t mean they’ve lost value. Stansfield (1985) notes that the main argument against dictation is that it’s passive and does not reflect the way we naturally learn languages. As newer, more progressive language teaching ideas grew popular in the US in the 1950s-60s, more traditional methods like dictation faced criticism and fell out of favor. And while dictation has gained steam in some world language teaching circles, it still suffers from these stigmas.

Like many things when viewed superficially, dictation faces pushback simply because we don’t know how to use it correctly and we fail to probe into its actual worth in our classrooms. Sutherland (1967) illustrates this principle succinctly:

The past abuses of dictation, it seems to me, have occurred mainly because instructors have, more often than not, used the technique incorrectly and at the wrong time. While I would agree that dictation can on occasion be used effectively in most language classrooms, such effectiveness depends to a large extent on (a) when it is used, i.e., at what stage in the sequence of language-learning activities, and (b) how it is handled.

Fortunately for you, reader, we’ll dive into both a) and b) with an extra c) knowing why we use dictation in this blog post. In order to understand actually integrating dictations into our language classes, we should understand why we should use them in the first place.

Why use dictations?

In the first post in this series of “Four Unique Ways to Use Extempore,” I highlighted the under-appreciated practice of reading out loud. One of its benefits is that it trains the eyes of learners to associate sounds to the script or alphabet of the target language (similar to how children learn to read English by sounding out words). Dictations, for that matter, train the ears of students, allowing them to grow more comfortable with new sounds, while also incorporating an added element: students have to confirm what they hear by writing it down. And while oral reading and dictations might seem like polar opposites, they both involve an aspect of language production. In oral reading, students produce oral output from what they read. In dictations, students produce written output from what they hear. Some might complain that “well, that output is coming from another source; they’re just copying the input! They’re not producing anything new!” And to that I say, “So what?” They are engaging with the language and producing it in a low-stakes environment, while at the same time training their eyes and ears to interpret the language.

A Cognitively Demanding Task

For students to complete a dictation, and to do it well, it requires balancing some intense cognitive processes. As the instructor is speaking, listeners have to “distinguish different sounds, make selection of lexis, constantly formulate expectancies concerning the incoming sounds and information based on their internalized grammar of the language, and record the speech in written forms as fast as they can” (Li 2020).

While standard dictations (we’ll look at modified versions below) do not reveal much about semantic comprehension, they offer insight into students demonstrating knowledge of what they hear. And why shouldn’t we assess that? After all, students have to know what they are hearing (body language and voice clues aside) before they can even begin to comprehend it.

In a word, dictations are hard, and they challenge many important areas of language learning, including short term memory, phonetic and lexical awareness, and spelling / typing skills.

Focus on Form

Students also benefit from dictations due to its emphasis on the language’s form. And yes, I know, function over form. BUT! We do not learn languages by pretending that grammar structures, spelling, regional differences in pronunciation, and other linguistic nuances are nonexistent. A language must have form in order for it to function, after all. When we focus on the form and intricacies of a language, we get a deeper understanding of how to process the many different types of input we receive.

When to Use Dictations

Realistically, you can use dictations at nearly any point in a language unit. Consider the following examples:

- At the beginning of a unit, use dictation to see if students can pick out new words that they haven’t learned. Based on the context of what they hear and write down, can they guess the meanings of new words?

- Alternatively, instead of an audio clip, use a video clip for dictation. See if students can use context clues to guess the meaning of words.

- Use dictations for basic practice or homework. Depending on language level, give students short or long passages to listen to and then write down.

- At the end of a unit, use dictation for a low-stakes assessment. When students have mastered vocabulary and relevant grammar patterns, have them illustrate this knowledge by completing a dictation.

- Dictations can be adopted into exit slips for quick formative assessments.

- Give a dictation as a warm-up to introduce new words or phrases.

What to Consider When Composing a Dictation

Like any other valuable assignment / language practice, a good dictation requires a concerted effort. Consider the variables that impact a dictation’s success:

- The type of text

- What text will you read? Think about the differences in reading a monologue, a dialogue, or a short narrative and how students will distinguish between them.

- Text length

- Remember: the longer the text, the more time students will spend writing, and (likely) the more times students will need to listen to the recording. When in doubt, lean on something shorter.

- Your reading speed

- This is a big one. Start slow. Then, as your students grow accustomed to your speed and doing dictations, gradually shift to reading at a more native / natural pace.

- Student language levels

- You can’t expect students to perform well on dictations if they only know 25% of the words in the text. Be aware of how much your students will comprehend.

Taking Dictations to the Next Level: Countering Language Shock

So far we've talked about the basics of dictations and their benefits and uses in the classroom. However, they can offer larger challenges and open new doors to students' linguistic insight.

Language teachers are faced with a conundrum in language teaching. We want our students to understand the language, hear it as we know it’s spoken with as little confusion as possible. The problem is that there are many instances where the language is spoken much differently outside of the classroom than it is in it. Yes, we use authentic resources, but even then, sometimes those resources are long, characters speak too fast and there’s too much new vocabulary. Thus, for a variety of reasons, sometimes the form we learn in school isn’t the same as the form we see in the real world.

When this happens, students will face severe language shock upon entering the target culture. Language teachers are well aware of culture shock, and many of us experience it when spending time in new places outside our traditional cultures. But how many of us have also experienced language shock? We spend hours upon years of time in the classroom in our native classrooms learning the target language, but upon arrival in the target country, we learn that the language sounds nothing like what we were taught! Pronunciations we’ve never heard, sounds being smushed together, and plenty of other surprises make us question everything. A Chinese friend of mine once told me about how he first came to the states knowing two basic questions: “How are you?” and “What are you doing?” Imagine his shock when he faced the question “How are you doing?” instead!

The idea of language shock has been around for a while, and there are literally books on the topic. Let’s look at two basic types of language shock and how we can use dictation as a remedy for these surprises.

Dialectal / Pronunciation Differences

For English learners, pronunciation differences most often appear when comparing British English, American English, and Australian English. Among other examples, consider how clearly you enunciate the r in 'car,' how you pronounce schedule, or whether the am from example rhymes with "mom" or "jam." In Spanish, the word taza can be pronounced "tatha" or "tasa" depending on where you're from. In Chinese, where can be "nǎlǐ" or "nǎr," depending if you are from the south or the north. For non-native speakers, regional pronunciation differences have to be learned. Dictation is one way to introduce our students to those differences.

Elision

Example two of language shock is elision. Whether or not you know what elision means, you use elision in your speech all the time. Take the phrases “I don’t know” and “What did you get?” With such common phrases, it’s no surprise that we prioritize efficiency over enunciation, and thus we often hear and say these phrases as “I dunno” (or grunts that resemble “I ’onno”) and “Whadja get?” So common is elision in parts of English speech that some (American) phrases like “What’s up?” have morphed into just “Sup?” Some call it lazy, but elision is a sign that languages are alive and always changing. Below are some examples in English.

| Written English | Elided Spoken English |

| Going to | Gonna |

| Want to | Wanna |

| I don’t know | Dunno |

| Did you eat? | J’eat? |

Spanish as well is no stranger to elision, particularly with the sinalefa phenomenon. In this scenario, when a word that ends with a vowel is followed by a word that begins with a vowel, the final and initial sounds elide, eliminating a syllable. Esa escuela, “that school,” is read properly with four syllables, not five, as EH/saes/KWEH-lah (see linked article).

Outside of the sinalefa, there are plenty of more examples of elision in Spanish. I’ve asked some of our native Spanish speakers here at Extempore, and they’ve given the following examples:

| Written Spanish | Elided Spoken Spanish | English |

| Voy a ver | Via ver | I’ll see... |

| Pues, eso | Poseso | Well, that (filler speech) |

| Tocado | Tocao | Touched |

| España | Epaña | Spain |

| Madrid | Madri | Madrid |

Finally, I’ve gotten my fair share of language shock from native Chinese speakers as I encountered dozens of cases of elision in Mandarin Chinese, particularly in Taiwan. To hear the first three examples within 12 seconds (!) of one another, check out the video below. Time stamps are in the chart below, next to each word for when it appears. The speaker is from Taiwan.

| Chinese Characters | Standard Chinese Pinyin | Elided Spoken Chinese | English |

| 非常 (1:14 - compare at 6:45) | fēicháng | fēi’áng | very |

| 等一下 (1:19) | děngyīxià | děng’yà | shortly |

| 大家 (0:10 and 1:26) | dàjiā | dà'ā | everyone / you all |

| 不好意思 | bùhǎoyìsi | b’ǎoyìsi | excuse me |

| 不要这样子 | búyào zhèyàngzi | biàojiàngzǐ | don’t be like that |

| 其实 | qíshí | qí’ír | actually |

| 不知道 | bùzhīdào | bu’ào | don’t know |

Upon first hearing these new sounds, many students will be shocked at these linguistic abominations. Remind your students, though, that elision is a natural part of language, and that they are equally guilty of not pronouncing every sound in their own speech. For native speakers, there is no “right” or “wrong” way to speak their language, and by learning about regional lexical and phonological differences, students can cultivate linguistic respect and tolerance.

Using Dictation to teach elision and pronunciation differences

When introducing examples of elision in your target language to your students, it’s important to first set goals. Before students can understand what is being said (the main goal of dictation), they have to know that elision exists. As such, you can start with noticing. Prepare a short audio file and its transcription, and have your students listen and read along. As they read and listen, students should find areas where they notice discrepancies in pronunciation against what they are reading. Are certain sounds not pronounced? Are words elided together? How different is this Spanish (or other relevant language) from what we’ve normally heard? Simply comparing written text to how it’s pronounced allows students to build linguistic awareness and strengthen listening skills.

After students have sufficient practice noticing differences, you can give more specific instructions. For example, have students listen for a specific number of instances of elision and/or pronunciation variations.

Once students are aware of pronunciation differences and elision, they’ll be ready for an authentic dictation from a native speaker.

As mentioned above, dictation serves many other purposes outside of noticing elision and pronunciation differences. And I can understand teachers of novice-level learners who might say that these linguistic idiosyncrasies are too much to focus on, particularly when the main goal is proficiency. Still, if we want our students to be prepared for authentic language, we cannot ignore these factors. If you’re scared of introducing them, take baby steps. For example, for each unit, choose one word / phrase / common instance of elision to highlight and set a goal alongside your other learning targets:

- By the end of our unit, students will know the word “piscina” has different pronunciations based on region, or

- Students will know that “going to” and “want to” are often pronounced as “gonna” and “wanna,” respectively.

Goals like these are the building blocks of linguistic awareness, and while you’ll never teach every example of elision and differences in regional pronunciation, you can teach your students to be aware of these differences and to become active listeners.

Wrapping up

The more I write about dictation, the more I see its parallels to oral reading. It’s so simple on the surface and yet such a demanding task for students, and they will quickly learn that dictation is much easier said than done (sorry — I couldn’t pass up the pun 😄).

Also like oral reading, dictations take students back to the fundamentals of language learning. They are tasked purely with listening and recording, nothing more. Moreover, the manifold ways to modify dictations allow instructors to accommodate for all language levels, whether focusing on basic words, rearranging spoken sentences, or challenging students to pick out pronunciation subtleties.

We learn how to write by reading, and we learn how to speak by listening. As students listen to a teacher's voice, process what they've heard, record that in written form, and check what they've written, they are fully engaging with the process of learning a second language. There's no reason not to use dictations in language classes.

Works Cited:

Li, L. (2020). Exploring the Effectiveness of a Reading-dictation Task in Promoting Chinese Learning as a Second Language. Higher Education Studies, 10(1), 100. doi:10.5539/hes.v10n1p100

Stansfield, C. W. (1985). A History of Dictation in Foreign Language Teaching and Testing. The Modern Language Journal, 69(2), 121-128. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1985.tb01926.x

Sutherland, K. K. (1967). The place of dictation in the language classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 1(1), 24-29. https://doi.org/10.2307/358590...

Grant Castner joined Extempore as Community Manager in August 2020. While managing social media and creating content with Extempore, he also teaches high-school level Chinese in Minnesota. An avid user of Extempore for language assessment, he’s always on the lookout for ways to improve his teaching practice. Have a question on how to adapt Extempore for your class? Just need help teaching? Contact Grant anytime at grant.castner@extemporeapp.com.